Understanding Tendinopathy: A Physiotherapist’s Guide to Recovery

Introduction

Tendon injuries are annoying and frustrating to deal with, whether you are an elite athlete trying to push performance, or you’re an everyday person just simply trying to do normal tasks. Often presented as a dull ache or stiffness that worsens with activity, tendinopathy is a common condition that can significantly affect your performance and quality of life.

Tendinopathy injuries occur frequently in sports and physical activity due to repetitive overload and poor recovery. But what is tendinopathy, and how can we manage it effectively?

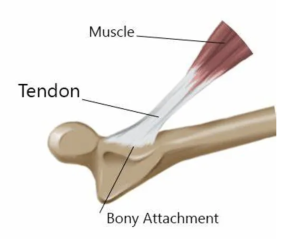

Normal Anatomy of Tendons and Their Function

Tendons are strong, fibrous connective tissues that anchor muscle to bone. Their primary role is to transmit force generated between muscle and bone, allowing movement of the body and postural support.

Tendons are composed mainly of collagen fibers to provide both strength and flexibility. Healthy tendons are able to withstand significant loads and adapt over time through loading and activity. However, when load exceeds the tendon’s capacity to recover either through overuse, poor biomechanics, or inadequate rest, injury can occur.

What is Tendinopathy?

Tendinopathy is a broad term used to describe a spectrum of tendon disorders resulting from mechanical overload. It typically involves chronic degeneration rather than acute inflammation (a common misconception). The condition affects the tendon’s structure which affects its ability to withstand and transmit load when performing activity.

An analogy easy to understand is thinking of a tendon as rope, and by constantly pulling at this rope at a high intensity with reduced recovery, this rope can start fraying, which is the tendinopathy taking place.

Symptoms often include:

- Localized pain (especially with activity or loading)

- Stiffness (commonly worse in the morning)

- Swelling or thickening of the tendon

- Reduced function or strength

- During activity, it can feel worse before and after, however better during.

Common sites for tendinopathy include:

- Achilles tendon (Achilles tendinopathy)

- Patellar tendon (Jumper’s knee)

- Lateral elbow (Tennis elbow)

- Rotator cuff tendons in the shoulder

Stages of Tendinopathy

Tendinopathy can be broken into stages, as described by Cook & Purdam’s Continuum Model:

- Reactive Tendinopathy – A short-term response to overload. The tendon thickens due to swelling but remains structurally intact. For example, moving house or performing an activity after a break (for example, running).

- Tendon Dysrepair – The tendon structure begins to break down with disorganized collagen and neovascularization (in relation to the analogy this would be when the rope starts to fray).

- Degenerative Tendinopathy – Long-standing injury with poor healing potential. Collagen is extensively damaged, and symptoms are chronic.

Each stage requires a different management approach, and presents differently between stages, which is why a professional diagnosis and personalized rehab plan are essential.

Management of Tendinopathy Injuries

Gone are the days of resting tendinopathy completely, modern physiotherapy management focuses on active rehabilitation. According to current research, the gold standard treatment is a progressive exercise-based program, tailored to the individual and the specific tendon involved (Couppé et al, 2015).

Key evidence-based management strategies include:

- Load management: Adjusting activity levels to reduce aggravation while maintaining as much function as possible.

- Exercise therapy: Gradual loading through strength-based movements improves tendon structure and function.

- Education: Helping patients understand the nature of tendinopathy reduces fear and promotes long-term adherence.

Exercise selection depends on the stage of tendinopathy, the individual’s pain levels, and functional goals. There are generally three key phases in rehab:

- Isometric exercises – Often used in early stages to reduce pain without overloading the tendon. For example, holding a calf raise for Achilles tendinopathy.

- Heavy slow resistance (HSR) training – This form of strength training (e.g., slow eccentric-concentric squats for patellar tendinopathy) helps stimulate tendon remodeling.

- Plyometrics and sport-specific loading – Introduced later in rehab to prepare the tendon for return to high-speed or high-impact activity.

All exercises should be pain-monitored, meaning mild discomfort is acceptable during rehab, but sharp or worsening pain is not.

Recovery Timeframe

Recovery from tendinopathy is not quick, tendon tissue heals slowly due to limited blood supply. While mild cases can improve in a few weeks, most cases require 8–12 weeks of consistent rehab, and more chronic conditions can take 3–6 months or longer.

Key to recovery is patience, adherence to the program, and understanding that load tolerance improves gradually.

Conclusion

Tendinopathy is a common but treatable condition that requires a well-structured rehabilitation approach focused on progressive loading, individualized exercise, and patience. With evidence-based management and a clear understanding of tendon physiology, recovery is absolutely achievable but it takes consistency, the right guidance, and time.

If you’re struggling with ongoing tendon pain or unsure how to manage your rehab, consider seeing a physiotherapist. We can assess your condition, identify contributing factors, and guide you through a tailored exercise plan to get you back to doing what you love pain-free.

References

Couppé, C., Svensson, R. B., Silbernagel, K. G., Langberg, H., & Magnusson, S. P. (2015). Eccentric or Concentric Exercises for the Treatment of Tendinopathies? Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 45(11), 853–863. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2015.5910

Cook, J. L., Rio, E., Purdam, C. R., & Docking, S. I. (2016). Revisiting the continuum model of tendon pathology: what is its merit in clinical practice and research? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(19), 1187–1191.

Written by: Brendan Micallef